When a fertility rate crash is not a crash

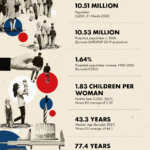

The story of Czechia’s fertility rate, which at 1.83 last year surpassed that of metropolitan France which has long had one of Europe’s highest rates, is a fascinating insight into its demographic history.

During the depression years of the 1930s uncertainty about the future pushed it below 2.1, the level a population needs to replace itself without immigration. Remarkably, it then shot right up beyond this during World War II, in part because Czechia was mostly spared the fighting and because having children was a way to escape being sent for forced labour to Germany.

The fertility rate stayed high during the early Communist years, which for many were ones of optimism. It then dipped below the replacement level between 1966 and 1972, and finally slipped below it for good in 1981. In 1989 it was 1.87, but it then plummeted to 1.13 a decade later. In that year, 89,471 babies were born, the smallest number in modern Czech history. Ever since it has been creeping back up. In 2021, there were 111,793 births in Czechia. In the first half of 2022, however, there were some 50,000 births meaning that this year, for reasons that are not yet clear, the birth rate looks set to decline by about 10 per cent compared with last year.

The complete collapse in the fertility rate after the demise of Communism happened across Central and Eastern Europe (CEE). These were years of economic turmoil and almost everywhere ones of intense hardship, unemployment, increasing mortality rates and high rates of emigration.

Research by Tomas Sobotka of the Vienna Institute of Demography, however, reveals that what was happening in Czechia was completely different. He argues that “the crash in fertility rates” was not really a crash at all, but rather the realignment of Czechia’s eastern European Communist-era marriage and childbearing patterns back to the Western European ones it had had before the war.

A woman born in 1965 typically had her first child when she was 20 or 21 years old, he says. But a woman born in 1990 “is typically having her first child when she is 29 and inbetween you have this transition when women and their partners were waiting longer before they had their first kid. So, in this transition period, fertility rates went down, in part not because people stopped having kids, but because they were waiting until they were older.”

Another reason why the age of having a first child in Czechia has shot up very fast, he explains, is that under Communism sex education was poor and the use of the contraceptive pill was low, so many first-time pregnancies were accidental. In 1990, only 4 per cent of women of childbearing age took it. This changed rapidly and so the numbers of unplanned births and abortions plummeted. Currently, about 30 per cent of Czech women of childbearing age take the pill.

Today, fertility is supported “by relatively generous family policies,” says Sobotka, “allowing flexible and well-paid parental leave for parents during the first three or four years of each child’s life.” Fairly egalitarian redistributive welfare policies have also helped keep “more social stability and avoided the worst of economic inequalities and excesses seen elsewhere in post-Communist countries.”