- Hans Weber

- December 18, 2024

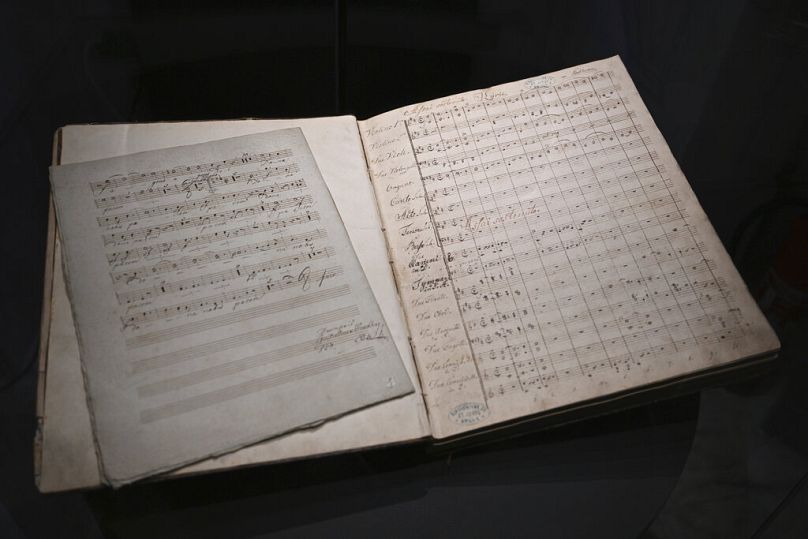

Czech museum to return Beethoven manuscript saved from the Nazis to its rightful owners

The manuscript ended up in the archives of the Moravian Museum in the Czech city of Brno to protect it from being stolen by the Nazis, as the Petscheks, once the richest family in pre-World War II Czechoslovakia, fled the country to escape the Holocaust.

The museum kept the autograph of the 4th movement of the string quartet in B-flat Major, op. 130 — a highly valued late quartet by the German composer — in its collections for more than 80 years.

Now, a local restitution law on the property stolen by the Nazis is making the return possible.

For the first time, the Moravian Museum curators have put the score on display for five days before it is set to be handed over to the Petschek family.

“The item itself has a fascinating collecting story,” says curator Simona Sindlarova. “The whole story reflects the history of Central Europe in the last 200 years.”

High-stakes lie to Nazis works, saves the manuscript

Details about how the family, whose wealth came mainly from the mining industry and business in the banking sector, acquired the piece after the Great War are unknown.

Beethoven composed the six-movement quartet in 1825-26, as part of his work on a series of late quartets commissioned by Russian Prince Nicholas Galitzin.

It premiered in March 1826 in Vienna’s Musikverein.

Museums, archives and libraries in five countries, including the Czech Republic, France, Germany, Poland and the US currently have almost 300 pages of the autograph among them in their possession.

Before the Petcheks took ownership, it is known that Beethoven, who died in 1827, gave the 4th movement to his secretary Karl Holz, while at least two other private owners in Vienna acquired it later.

An attempt to send the piece abroad by mail at the Petchek family’s request in March 1939 failed during the Nazi occupation of Czechoslovakia, drawing the attention of the Gestapo.

It is then that “the expert from the Moravian Land Museum was called in to verify the authenticity of the autograph,” explains Sindlarova.

“He immediately recognised its veracity, but in order to protect it from the occupiers, he and others involved denied it was authentic.”

The lie that might have cost him dearly worked, and the Germans allowed the museum to keep the piece in its collections.

Most of the family’s businesses and possessions were seized by the Nazis and nationalised by the Communist regime after the war.

From their home in the US, Frantz Petschek tried to get the score back, but his efforts were futile amid the post-war division of Europe and the creation of the Iron Curtain.

Eventually, a deal was signed on 3 August to transfer ownership from the museum to the heirs.

“Absolutely, it rightly belongs to the Petscheks. It is a question what will be next. A new chapter of this fascinating collector’s story is here,” says Sindlarova.

Such a happy ending has not always been possible.

Earlier this year, the London-based Commission for Looted Art in Europe concluded that “despite the Terezin (Theresienstadt) Declaration on restituted artworks, the prospect of looted art being returned was distant.”

It reviewed the progress made since a 2009 non-binding resolution where delegates from more than 40 countries urged governments to make every effort to return former Jewish communal and religious property unlawfully confiscated.

The Commission also recommended all the countries address the issue of private buildings and land seized illegally by the Nazis and their collaborators.

Its guidelines encourage making it easier for foreign nationals to claim back property.

Recent posts

See AllPrague Forum Membership

Join us

Be part of building bridges and channels to engage all the international key voices and decision makers living in the Czech Republic.

Become a member